Options for different electoral systems in the future Bangsamoro Region

- Details

- Blog Content

- Hits: 4431

This paper was presented by Dr. Peter Koeppinger at the Seminar of the Bangsamoro Transition Commission on the Ministerial Form of Government and Electoral Systems in Cotabato City on August 12th, 2013. Dr. Peter Koeppinger is an international expert on government systems and the current resident representative of Konrad Adenauer Stiftung in the Philippines.

This paper was presented by Dr. Peter Koeppinger at the Seminar of the Bangsamoro Transition Commission on the Ministerial Form of Government and Electoral Systems in Cotabato City on August 12th, 2013. Dr. Peter Koeppinger is an international expert on government systems and the current resident representative of Konrad Adenauer Stiftung in the Philippines.

“The electoral system shall allow democratic participation, ensure accountability of public officers primarily to their constituents and

encourage formation of genuinely principled political parties….” ~ Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro (FAB)

The FAB requests that the electoral system has to ensure accountability of public officers primarily to their constituents.

In a general way this will already be met in the ministerial form of government by the direct accountability of the government and its members during the whole legislative period to the members of the parliament, who are the representatives of the citizens.

But in a more specific way this indicates also the need to select an electoral system in which at least a majority of members of the parliament are representing specific constituencies.

The request of the FAB that the electoral system shall “encourage formation of genuinely principled political parties” is on one side related to the characteristics of a ministerial form of government.

Because what would be the criteria to hold the government accountable for the members of parliament if not the thematic issues and objectives, built on the ideology and principles of the majority parties, promised to the voters before the election?

And how could the members of the majority parties, supporting and holding accountable their government, act as a more or less unified group, if they consist only of personalities and patrons from their respective areas?

But how can the electoral system encourage the formation of such “genuinely principled political parties”?

Definitely a system, in which all members of parliament are just elected in their respective district by majority, is prone to be dominated by patrons and personalities, and a genuinely principled political party – if existing – cannot play a relevant role.

Therefore the electoral system has to include selection mechanisms for the candidates, in which their respective party, beyond single strong leaders in certain districts, decides with all its members in a democratic way on its candidates.

This however leads to another necessity: The accessability for political parties to elections in Bangsamoro has to be bound on the existence of normal citizens as party members – beside political office holders and candidates as potential “beneficiaries” from the elections – and on the existence and compliance with effective internal democratic decision making and selection procedures in these parties.

Preliminary remarks:

The decision on the size of the parliament (number of its members) is important, as it can support or limit the quality of democratic participation and the formation of genuinely principled political parties. In the actual ARMM with about 3,32 Mio inhabitants (statistical data from 2011) the Legislative Assembly counts 24 members. With the possible inclusion of Cotabato and the City of Isabela and some areas in Lanao del Norte in the future Bangsamoro and the high population growth the population in Bangsamoro at the time of the first elections in 2016 might increase to about 4.6 Mio inhabitants. International Standards for regional parliaments indicate that the number of inhabitants represented by one member of parliament should not be more than 100,000 in order to make interaction between the constituents and their elected representatives not too difficult. A number of 46 members of the parliament of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region could be adequate.

The population of the Bangsamoro area is highly diverse. Among the Muslim majority are different tribes, living mainly separated in the island provinces (Basilan, Sulu, Tawi Tawi), Lanao del Sur and Maguindanao. Furthermore Christian settlers and different groups of Indigenous People community are spread over the whole area, being small minorities or even dominant majorities in some barangay or even municipalities.

The quality of democratic participation will depend on the design of an electoral system which provides them with the opportunity of being represented in a fair way in the regional parliament, which – in the ministerial system – is the centre of the state power.

The term (legislative period) for which the regional parliament is elected should be longer than 3 years. International standard for such parliaments are 4 or 5 years. However this decision should be considered also in connection with the elections for the local governments in Bangsamoro.

As the term for local elections is expressively fixed at three years in the Constitution of 1987, it would be probably necessary to amend the Constitution, if the term for local elections in Bangsamoro should be prolongated also to 4 or 5 years.

A solution could be to fix the term initially on 3 years for both the regional parliament and the local councils in Bangsamoro and to amend it to 4 or 5 years whenever a respective amendment of the Constitution can be achieved.

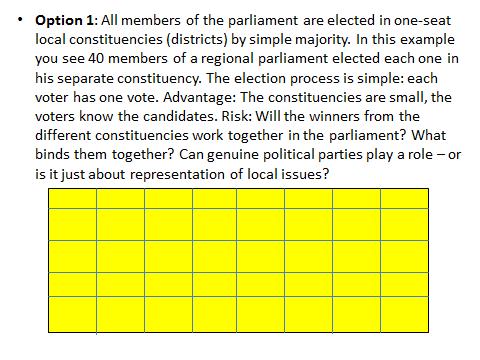

First judgement: This option would create in theory a perfect system of direct accountability of the elected public officers to their local constituencies. But this is only true if these local representatives would be selected by genuinely principled political parties, build on membership of normal citizens, who would hold accountable the elected representatives after their election and monitor their performance.

In the Bangsamoro reality this option would strongly favour the grip of local dynasties or dominant families on the representation in the powerful regional parliament. It would make it very difficult for genuinely principled political parties, organized region wide in Bangsamoro, to have influence on the selection of successful candidates in the districts and to play a strong role in the orderly management and performance of the Bangsamoro parliament.

It would also make it impossible for minorities spread over the region to be represented in the regional parliament as long as they do not have a majority in one of these districts.

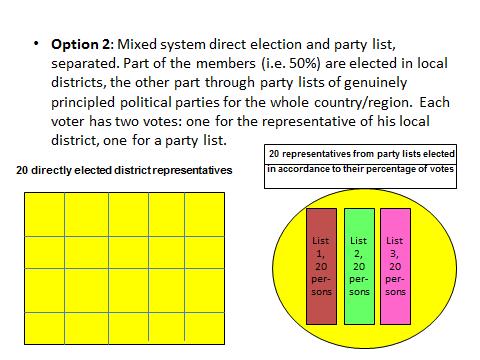

First judgement: This option would still contain a strong element of direct accountability of half of all members of parliament to their local constituents – still with the disadvantage in reality that it would provide the local dynasties and dominating families with the possibility of strong representation in the regional parliament.

However in this option the formation of genuinely principled political parties would be encouraged because they would have the opportunity to create strong party lists along their respective principles and advocacies beyond the borders of the different provinces for the whole Bangsamoro region.

And scattered minorities would have the possibility to be represented or through inclusion in the party lists of strong regional principled parties – who would also compete for the votes of these minorities in order to achieve majorities in the regional parliament – or through their own minority party list, which could win a seat with less than 3% of the total votes in Bangsamoro.

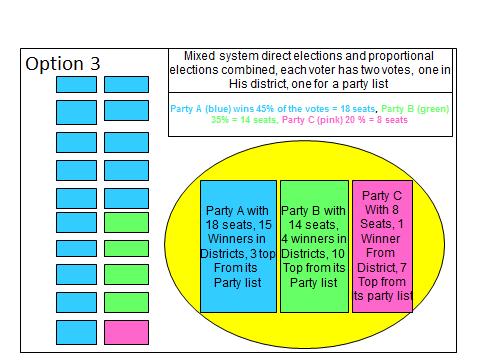

First judgement: Similar like in option two this option has the disadvantage that it could still leave much room for local political dynasties to dominate the regional parliament. And similar to option two this option has the advantages that it provides genuinely principled political parties with the opportunity to play an important role and that it provides scattered minorities in Bangsamoro with the opportunity to be directly represented in the regional parliament.

Furthermore in comparison with option two it has the advantage that it is even more inclusive because all seats – not only half of them – are distributed in accordance to the proportional representation system.

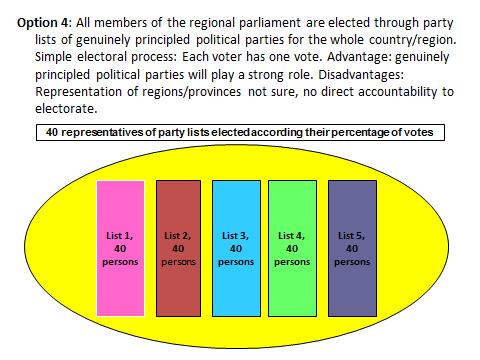

First judgement: This option would strongly encourage the formation of genuinely principled political parties organized throughout the whole Bangsamoro area. They would dominate with the candidates on their lists – elected in (hopefully!) internal democratic procedures by the members of these parties – the powerful regional parliament.

The disadvantage of this option would be that if a strong and winning political party with its support mainly coming from part of the Bangsamoro region would put only or mainly candidates from this part of the region on the top of its list, the demand of the FAB on an electoral system which “ensures accountability of public officers primarily to their constituents” would not be met, and part of the population of Bangsamoro would not feel to be represented in its political decision making institutions.

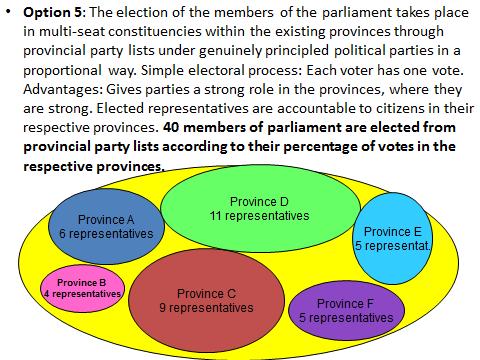

First judgement: With a supposed number of 46 members of the Bangsamoro parliament this would lead, following the statistical population data from 2011, to a distribution of 12 seats in the Maguindanao Province District, 12 seats in the Lanao del Sur Province District, 9 seats in the Sulu Province District, 5 seats in the Basilan Province District (including Isabela), 4 seats in the Tawi Tawi Province District and 4 seats in the Cotabato district.

In this option on one side the accountability of public officers primarily to their constituents would be ensured – as the lists are presented and voted on in the different provinces so that the winning candidates would feel accountable to these constituencies.

On the other side this option would strongly encourage the formation of genuinely principled political parties in Bangsamoro, as it would be these parties with their members, who elect the candidates in their respective multi-seat districts, and it would be more difficult for the local political dynasties and dominating families to dictate whole the provincial list of the party than to do that in smaller one-seat constituencies.

The formation of principled political parties would also be encouraged under this option by the fact that only with party organization along principles and ideologies a party would have a chance in the diverse ethnic and tribal reality of the different provinces in Bangsamoro to win seats in all parts of the region and to achieve influence or even a majority in the regional parliament.

The multi-seat constituencies would also provide scattered minorities in the different parts of Bangsamoro with the opportunity to be included into the representation in the powerful parliament – namely through their inclusion in the party lists of strong regional principled parties – who would also compete for the votes of these minorities in the provinces, where they are relevant, in order to achieve majorities in the regional parliament.

Conclusions:

Different from the situation in countries with existing strong principled political parties, built on dues paying members, the option 1 (direct simple majority vote in one-seat districts) would not produce stable majorities in the Bangsamoro regional parliament and therefore would not provide the government of the region with continuous support and stability, because it would be a multitude of local dynasties and dominant political families who would be the main beneficiaries of such an electoral system.

The necessity to create stable majorities in the parliament for the stability of government – which is an important challenge in the ministerial form of government – requests an electoral system, which is strongly encouraging the formation of principled political parties and the control of the regional parliament by them.

This can be in form of one dominant party or by a coalition of two or three of them, being inclusive also for the diverse groups and minorities in the whole region through their principles and ideological orientation instead of one issue or one group or one locality advocacies.

Under this aspect of creating stability and inclusiveness of the political system of Bangsamoro as a precondition of its success and sustainability options 2, 3 and 5 seem to have clearly more advantages than options 1 and 4.